The Perverted Yield Curve

There has been some hype in the media about the yield curve inverting and how that often leads to a recession. I have three main points to make:

First, the yield curve has not inverted, it has been perverted.

Second, the US treasury yield curve has become perverted by huge distortions and imbalances in the greater global economy.

Third, it's all relative.

With regard to the first point:

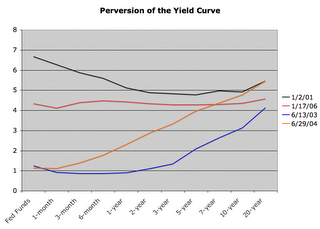

The following chart shows the yield curve at certain key points in time:

1/2/01 was when the curve was most inverted before the 2001/02 recession.

6/13/03 was when rates were lowest, during the deflation scare.

6/29/04 was when the curve was steepest, one day before the Fed started its current series of rate hikes.

1/17/06 was when the curve became most inverted early in the year.

When prices change, there is money to be made. It follows that those with the power to move rates have the power to make money for the well positioned. Some might argue that fluctuating interest rates reflect uncertainties in the economic landscape. I contend that large movements in interest rates are controlled to meet the political and financial goals of key institutions. I use the word "perverted" to describe the curve, rather than "inverted" because I think the yield curve is intentionally distorted by the Fed and Wall St. institutions.

Let me suggest that the yield curve became "inverted" because the Fed intentionally tightened interest rates too much during the 2000 presidential campaign to help undermine the Democratic candidacy. With the stock market crashing, the Fed continued to boost interest rates into May and kept them high until after the election. Soon after the election was over, the Fed conducted 2.5% worth of rate cuts in 5 months.

Let me suggest that the yield curve became lowest in 2003 to help stimulate the economy for the 2004 campaign. The stock market had bottomed in October of 2002, but the Fed cut rates another 0.75% to absurdly low levels and stoked fears of deflation. As ridiculous as that sounds in the era of fiat money, the markets reacted to it.

Let me suggest that the yield curve became steepest in 2004 to help stimulate the hedge fund industry as a way to boost Wall Street trading volumes and profits. Short term profits became automatic as fund managers were able to borrow at ultra low rates an invest in any asset class imaginable. Of course this created huge long term risks, as there are always too many managers eager to seize short term profits.

Let me suggest that the curve has become "perverted" now as the Fed desperately seeks to prop up the dollar without wrecking the carry trade excesses of the last 3 years. The carry traders have their backs to the wall, as their borrowing costs have risen and they can't afford to have bond prices fall on rising long bond yields. Meanwhile, the US government's debt service has risen to over $400 billion per year. Meanwhile, the mortgage industry is feeling the squeeze as borrowers get scared away by rising rates. Long bond rates must stay low, or the system unravels. Active intervention is needed to override natural market forces.

The 2000-2001 inversion correctly forecast falling short-term rates into 2003, but the current perversion isn't really forecasting anything, as far as I can tell. One could argue that the curve is calling for an extended period of unchanging interest rates after a few more hikes, but then the entire yield curve would still be too low relative to inflation.

In recent months, interest rates have been allowed to move up gradually. I expect that a rapid rise would break the system, while a slow rise keeps the derivatives markets intact and the dollar afloat. Here's a chart of the yield curve at various times this year:

The curve has steepened and perverted alternately as pressure has built on long bond yields and then subsided. January 17th, saw the maximum perversion before treasury demand in February and March drove rates up. Now the curve is perverted again, but that may be difficult to maintain. We'll see how Paulson does as head of the treasury.

With regard to the second point:

My take is that yields are suppressed by artificial demand on the short end and in the 5-10 year bonds and by limited supply on the long end. There may be many potential explanations for this, including:

1. Derivatives underwriters may have high demand for 5-10 year treasuries. There has been an extreme expansion of the mortgage market based on surging home prices, 0% down mortgages and cash-out refinancing. This has mainly been fueled with short term financing and many of the investors in mortgages have sought to hedge away interest rate risk by purchasing interest rate swaps and other derivatives. The underwriters have then sought to balance their own risks by purchasing 5-10 year treasuries. This has had the added effect of keeping mortgage rates down, with fixed rate mortgage rates linked closely to 10-year treasury yields.

2. The Government has created a shortage of supply on the long end. The US government has been seeking to bring down interest expense on the national debt by issuing more short term securities relative to long term securities. They've done this to the extreme point that the entire range from 6-months to 10-years is now essentially flat. There should be much more risk associated with the longer term bonds based on the risks of rising inflation and even potential default in a nation with over $8.4 trillion in debt and a $700+ billion current account deficit. Suppressing long term yields through reduced supply creates further risk of higher rates in the future as too much debt will be rolling over in near future. The government is sacrificing future security for lower interest payments today.

Composition of Marketable Securities

November 2005...November 2000

Bills............983 B.......682 B

Notes.........2339 B....1590 B

Bonds........516 B.......629 B

TIPs............327 B......121 B

FFB................0 B.........15 B

Total..........4166 B.....3037 B

% Bills........23.6%......22.5%

% Bonds....12.4%......20.7%

Bills are 1-year or less when issued.

Notes are 2 to 10 years.

Bonds are more than 10 years.

There is an added short term economic benefit to suppressing longer term yields in the way the mortgage financing and hedging cycle gets a boost, prolonging the housing boom. Of course the potential for sharply higher rates in the future means that a subsequent housing bust could be much worse.

3. Yield chasers could be driving demand for longer term notes and bonds. Pension managers needing to produce high returns to meet payment expectations can come closer with higher yielding long term notes, even if the risks are greater. Similarly, mutual fund and hedge fund managers hoping to outperform their peers can do better most of the time by taking larger risks.

4, 13 and 4-week bills could be a low-risk and flexible storage of wealth for foreign investors more than a pure investment. Many investments in the US economy have been net losses recently for foreign investors, but the total amount of wealth outside the nation continues to grow as the trade gap continues. From a national perspective, foreign governments and central banks may see economic growth and profitability as the main goals, and through willingness to accumulate US debt and invest it at low yields they further their narrower goals. It doesn't matter if the earnings from their wealth are high as long as the earnings from their exports are high.

5. Surplus money supply may be boosting demand in the short durations. Extreme amounts of money creation by the Fed and banking system and a lack of suitable investment opportunities have forced surplus cash into money market accounts, which in turn is largely invested in short term treasury bills.

The more money the Fed helps create, the more money is forced into treasuries, causing the "conundrum" of low treasury yields in spite of a rising federal funds rate. The 4-week is now about 75 basis points below the federal funds rate even though more rate hikes are expected going forward. Has this ever happened before?

The yield is out of whach from 6-months to 3 years, but why would anyone want to buy those bonds at these prices? It takes a hidden agenda to want to buy the short-term and long-term treasuries, and there isn't a very good reason for big players to invest in those middle range options.

And finally, with regard to the third point:

The Fed did a study awhile back and discovered that the best predictor of recessions was the inversion of the yield curve. OK, fine, but:

1. An official recession is an arbitrary measure of a slowdown in economic growth (i.e. 2 quarters of negative real growth). If GDP slows to 0.1% for 20 straight quarters, that's not officially a recession, but it sure is a bad economy. What really matters (at least in the short term) is the rate of growth, not the term recession.

2. Inversion is also arbitrary measure. When the yield curve tightens (whether or not it inverts) that discourages money supply expansion by rendering the carry trade less profitable. That tends to reduce the rate of economic growth. (This makes the continued rapid expansion of the money supply especially suspicious.)

3. There are of course other important measures of economic stimulus that can outweigh the yield curve. The most important ones, IMO, are money supply expansion and the amount foreign investment capital flowing into the country. Both of those were very high in 2004, and based on the government's reports (if you believe them) they trumped the tightening of the yield curve to produce continued economic growth. With foreign investment weakening, however, money supply growth has been the primary fuel keeping the economic engine running. The longer term cost of this is inflation, however, which can wreak widespread economic damage if it gets out of hand.

<< Home